Australia can become a green hydrogen and green iron powerhouse. But cannot do it alone.

Recently our weekly wraps have focussed on some essential use cases for green hydrogen. In April we wrote about green fertilisers and green shipping. This week, we explore the outlook for green iron and green steel, with a particular focus on Australia and its trade with the Asia Pacific region.

Australia is holding its federal election tomorrow, Saturday 3 May. A key challenge for whomever takes office will be to catalyse a new era of sustainable energy and resource exports. Australia is ideally placed to leverage low-cost renewable electricity to produce green hydrogen and supply green iron to the wider region if the right policies are put in place. The resource and energy transition required cannot be accomplished by industry and markets forces alone, nor by governments acting unilaterally. It will require an almost unprecedented pact that unites governments, industry, investors and civil society in a genuinely just and sustainable transition.

Australia’s three largest exports are iron ore for steel making (worth circa AUD 120 billion per annum), LNG mostly for electricity generation (80 billion) and thermal and metallurgical coal (80 billion) mostly for electricity generation and steel making respectively. The largest customers are in China, Japan and South Korea. Iron and steel making is a key focal point.

As Dr Ross Garnaut, former Australian Ambassador to China and the current Director of the Superpower Institute has noted: “Japan, Korea and China import huge quantities of Australian iron ore and coal and put them together to make iron metal, releasing greenhouse gases as a waste. Conversion of Australian iron ore into iron and steel produces about 4 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions — more than three times the emissions from everything we do in Australia”.

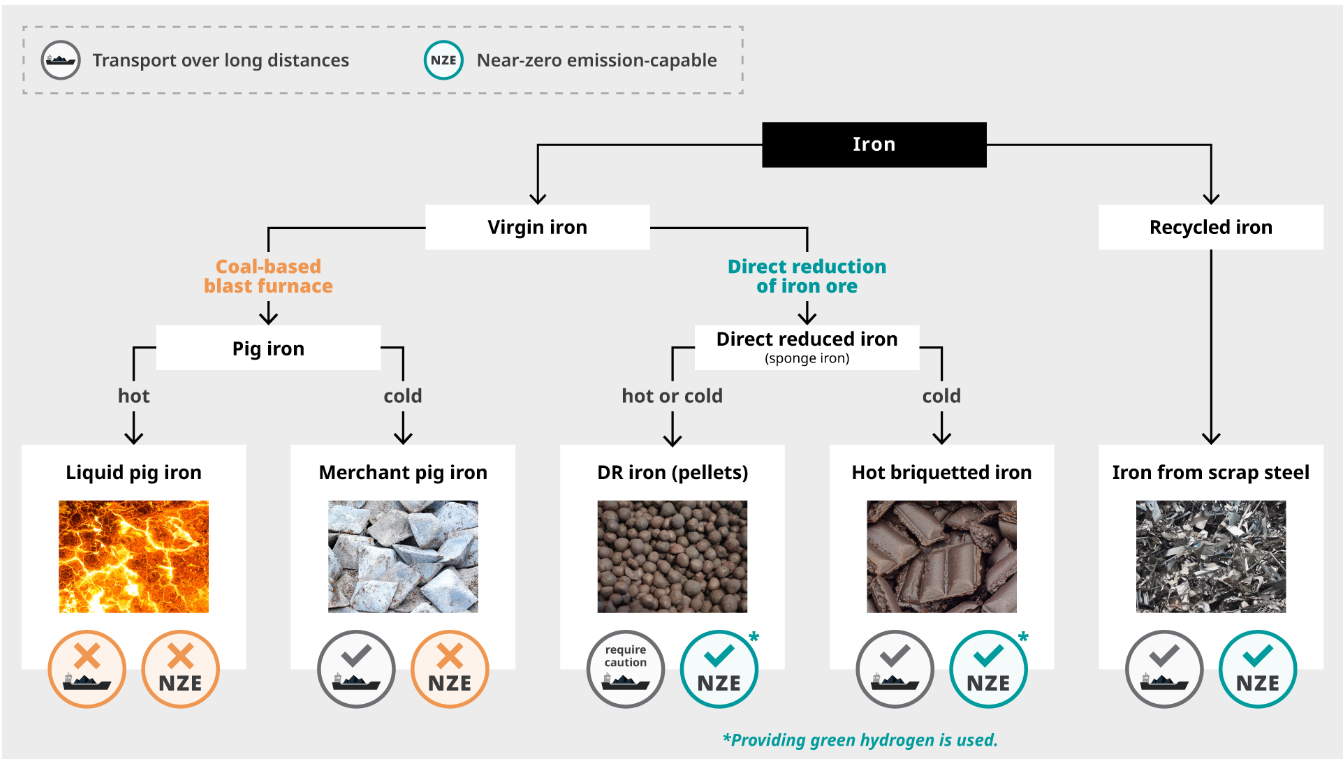

Fortunately, there is a more sustainable way forward where both sides of the trade can benefit. Green iron trade is key to catalysing the decarbonisation of the steel industry, and Australia is ideally placed to help lead this transition. Ironmaking and steelmaking often occur in the same place, where iron ore is reduced to iron and molten iron is used to make steel. In this excellent explainer, SteelWatch explore how to decouple iron and steel production by transporting green iron:

Historically, ironmaking and steelmaking have been done on the same site, known as an ‘integrated steel plant’ and energy considerations help explain why. Proximity to coal or gas suppliers has mostly driven the location of many coal-based blast furnaces and fossil gas-DRI plants. Locating the steelmaking directly onsite with the ironmaking enables energy savings: the hot iron coming out of ironmaking goes straight to steelmaking, avoiding the need for reheating. In the case of coal-based blast furnaces, they also release excess energy which steel plants have learned to capture and reuse. Looking ahead, access to renewable energy will increasingly shape locations of green iron production. Since green H2-DRI relies on the availability of green hydrogen made with renewable electricity, ironmaking will be pulled to regions with greater renewable electricity generation capacity, particularly those that also have iron ore.

Figure 1: Classification of different types of iron used for steelmaking, SteelWatch, 23 April 2025

Australia has all the ingredients necessary to supply this market: large reserves of low cost iron ore (both high quality magnetite and lower-quality hematite), low cost renewable electricity generation capacity, and the potential to produce some of world’s cheapest green hydrogen. In addition, Australia has extensive experience with large scale, export-oriented resource and energy projects including the necessary legislative, regulatory, engineering and financial expertise. Australia also has a reputation as a stable safe haven for resource sector investment, and strong trade relationships with Asian markets.

So… what are we waiting for? There are still some major challenges to navigate. First, there are technological challenges that need to be resolved. While some the processes are well understood or have been piloted at a small scale, the viability of large-scale green iron production – leveraging large quantities of iron ore, renewable electricity and green hydrogen - has not yet been demonstrated. While this is surely solvable, there are also some major economic barriers. Put simply: the demand for green iron (including a willingness to pay a green premium for a near zero emissions product) is insufficient to justify large scale investment. Green steel is too expensive in part because conventional steel is (artificially) too cheap. In most countries, the steel (and hydrogen) industries can emit millions of tonnes of greenhouse gases without penalty. And yet, even in countries where steel making is uneconomic, the industry receives large government subsidies. As Ross Garnaut notes: “Markets won’t work for economic development unless governments block economic transactions that impose large costs on others, or apply taxes that recoup for society the damage done to others, or subsidise competing activities... we won’t get anywhere near net zero in Australia or the world as a whole without mandatory Government action—a tax on carbon emissions equal to the social cost of carbon, or bans on activities that generate emissions, or subsidies for competing zero-emissions activities”.

In the maritime sector, we have seen a significant step forward with the International Maritime Organization’s draft regulations to reduce emissions from global shipping. Unfortunately, there is no equivalent organisation covering the steel industry that could impose similar measures on a global basis. Europe’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) are an important global benchmark. By putting a price on emissions associated with iron and steel produced in countries outside the EU, CBAM encourages other countries to implement similar measures to ensure market access. Japan is piloting a phased carbon market through the GX-League and GX-ETS, combining voluntary corporate participation with planned regulatory enforcement to support its 2050 net-zero target. Korea’s K-ETS has been operating since 2015, although there are concerns that free allowances for the steel sector are too generous, and that purchasing additional allowances is cheaper than investing in low-carbon technologies (and selling surplus allowances).

Garnaut highlights another important externality: “Innovation generates benefits that the investing firms cannot capture for themselves. Pioneer investors in new ways of doing things show others what works and what is not worth trying. They make costly mistakes that followers avoid. They generate knowledge from which followers benefit”. He concludes: “we don’t get enough innovation unless governments provide financial support for it”. Here, there have been several significant developments. The Australian Government is investing $4 billion in the Hydrogen Headstart program, which provides revenue support for large-scale green hydrogen projects through competitive hydrogen production contracts. Australia has a Hydrogen Production Tax Incentive to incentivise green hydrogen production with a time-limited and uncapped refundable tax offset of AUD $2 per kilogram of green hydrogen produced for up to ten years, between 1 July 2027 and 30 June 2040 for projects that reach final investment decisions by 2030. The government has also announced a AUD 2.4 billion package to support the Whyalla Steelworks, including $1.9 billion to invest in upgrades and new infrastructure, expected to include a shift to green iron and green steel production. On the “demand side”, the Japanese Government is providing important leadership, including a low-carbon steel tax credit, a clean energy vehicle green steel subsidy, and the promotion of Green Steel as a product with a low carbon footprint (CFP). These initiatives are welcome but are not yet sufficient to catalyse the changes that are needed.

Another challenge is the strategic importance of the steel sector, especially its links to construction, transportation and defence. While supporting innovation can create new jobs, there are also concerns in steel making countries that importing green iron will lead to job losses. SteelWatch estimate that ironmaking accounts for less than 10% of jobs in the steel value chain, but that “net jobs will rise and fall at different points in the value chain and different locations … and there are no robust estimates yet of total effect”. In principle, there is board support for a just transition strategy that supports affected workers, but putting this into practice and creating “win-win” outcomes is much easier said than done.

Figure 2: Decoupling iron and steel production by transporting green iron, SteelWatch, 23 April 2025

Finally, a green iron industry will not emerge without robust standards and certification. GH2 recently completed a review of the existing standards and certification schemes in the iron and steel industry. While there has been some important progress on agreeing methods to measure greenhouse gas emissions, most standards and certification schemes do not sufficiently prioritize net zero aligned production pathways. While there is broad based agreement that “a common understanding of existing and emerging definitions for near-zero emissions steel production is needed” (Steel Standards Principles, 2024) there is also a tendency to avoid setting specific thresholds that are clearly aligned with net zero commitments (nationally determined contributions). There is a clear risk that some the leading standards will lend credibility to iron and steel projects and products with unsustainable emissions, crowding out genuinely green iron and green steel.

In addition, most standards and certification schemes neglect essential sustainability criteria, including environmental impacts and alignment with a just transition. GH2 is working on several fronts to address these issues, including efforts to strengthen existing standards and regulations and by promoting best practice, especially on key issues related to the utilisation of hydrogen in iron and steel making. As in other sectors, a key concern is the methods used for measuring the emissions associated with natural gas utilisation. Most iron and steel standards use default values and/or national averages that can significantly underestimate upstream CO2 and methane emissions. GH2 is pushing for stricter standards on monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV). MRV is also crucial where projects make use of carbon capture and storage, especially given the poor track record of CCS projects. Another key consideration is addressing the integrity of renewable electricity utilisation, i.e., what types of electricity utilisation qualify as zero emissions. Finally, GH2 is active in explore the potential to use mass balance and book and claim certification systems to catalyse green iron markets. To sum up, while Australia can take steps to promote green iron supply – e.g., by supporting early movers and pilot projects – it is clear that a large and sustainable trade will not emerge without sustained engagement on the “demand side” to develop trade that is mutually beneficial.

A priority for the incoming Australian government will be to work with countries (especially in Europe and North Asia) that are genuinely committed to ending unsustainable practices and supporting sustainable alternatives. As SteelWatch concludes: “Decarbonising iron and steelmaking means more than simply replacing coal-based blast furnaces with H2-DRI plants. It requires strategic thinking and recognising that certain disruptions – like where iron is produced and by whom – are not just inevitable, but essential for accelerating decarbonisation”.

We agree. We look forward to supporting the next government in Australia, both on domestic measures to catalyse these new industries, and to supporting ambitious efforts in the Asia Pacific region and beyond.

Sam Bartlett,

Director for the GH2 Standard, GH2